Introduction

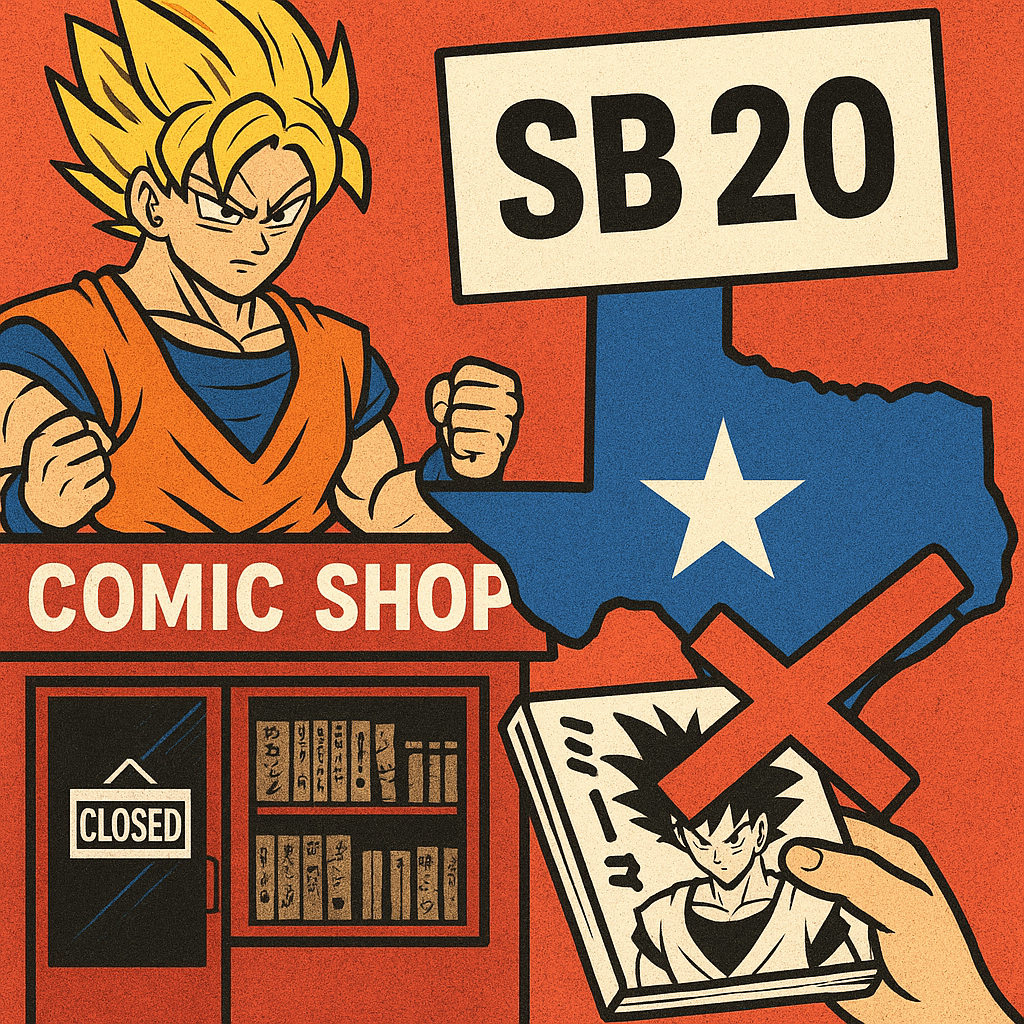

A new Texas law intended to crack down on obscene material is having ripple effects far beyond the targets many people imagine. Senate Bill 20, often referred to as SB20, includes language that touches everything from artificial intelligence imagery to sexual content in books. That breadth is now prompting retailers to second guess what they can safely stock. One comic shop manager in Weslaco reportedly pulled several Dragon Ball volumes as a precaution, not because he believes the series is obscene, but because the statute’s vagueness raises real risks for small businesses.

This article explains what SB20 is trying to do, why its wording worries retailers, how the Dragon Ball situation became a flashpoint, and what the broader consequences could be for comics, manga, libraries, and creators. You will also find a plain language overview of how obscenity is usually judged in the United States, why vagueness matters in speech laws, and practical options communities can consider when good faith confusion collides with popular culture.

What SB20 Tries To Regulate

The stated goal

Texas lawmakers advanced SB20 with a clear aim: limit the sale or display of obscene material, including sexual depictions of minors and certain explicit content that can appear online or be generated through artificial intelligence. The bill’s authors framed it as a child protection measure. Supporters often describe it as a necessary update for a world where content moves quickly across platforms and where sophisticated AI can produce convincing images in seconds.

Why the law reaches bookstores and comic shops

Retailers live at the intersection of art, storytelling, and commerce. Because SB20 is not confined to online platforms, the practical burden of compliance can fall on local stores that serve families, teens, and adult readers alike. The technical terms in the statute require shop managers to make judgment calls that lawyers and judges sometimes struggle to agree on. When livelihoods are on the line, many small business owners default to caution.

The Dragon Ball Flashpoint

What happened in Weslaco

In Weslaco, the manager of a local comic shop removed certain Dragon Ball Z volumes from the shelves. His reasoning was simple: some gags and brief visual jokes in classic manga can be suggestive or nudity adjacent, even when used for humor rather than titillation. He concluded that leaving those volumes out could invite complaints or worse under SB20. So he pulled them while he assessed the risk.

Why Dragon Ball of all things

Dragon Ball sits at a unique crossroads. It is globally beloved, broadly all-ages in spirit, and often shelved alongside teen titles. Yet its earliest volumes occasionally include cheeky humor that plays differently across cultures. There is no serious argument that Dragon Ball is pornography. The concern is not about the series’ core identity. It is about the uncomfortable gap between a decades-old comedic bit and a modern statute written to police sexual depictions under threat of penalties.

What the removal signals

The Weslaco decision is not a verdict on the manga’s value. It is evidence of a chilling effect. When laws are broad, people change their behavior to avoid even the possibility of becoming a test case. That is the textbook definition of a chill on expression. It does not take a government agent seizing a book to suppress speech. It only takes enough uncertainty that retailers withdraw content voluntarily.

Obscenity, Minors, And The Law: A Practical Primer

The Miller test in everyday terms

In the United States, “obscene” content sits outside First Amendment protection. The Supreme Court’s Miller test asks three big questions. One: would the average person, applying contemporary community standards, find that the work appeals to prurient interest. Two: does the work depict sexual conduct in a patently offensive way as defined by law. Three: taken as a whole, does the work lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. All three must be satisfied for a work to be legally obscene.

Dragon Ball plainly carries serious artistic and cultural value. It has influenced generations of artists, athletes, and storytellers. That matters under the third prong. The first two prongs are likewise context heavy. A fleeting gag does not convert an entire volume into obscene material. But shop owners are not courts. They do not get the luxury of a settled ruling in advance.

Content involving minors

Another layer involves any sexualized depiction of minors, which is treated far more strictly. Legislatures aim to prevent exploitation, including drawings that could encourage harmful behavior. Even here, however, context and definition matter. Is the depiction explicit. Is it lewd. Is it comedic and nonsexual in its framing. Those are not philosophical questions. They are the difference between lawful satire and prohibited material. Vague drafting increases the likelihood of disagreement.

Why vagueness matters

A law is unconstitutionally vague if people of ordinary intelligence cannot understand what is prohibited. The remedy for vagueness is precision. That means clear definitions, concrete examples, safe harbors for works with established artistic value, and processes for challenging questionable designations. Without those guardrails, well-meaning sellers err on the side of removing more than necessary.

The Retailer’s Dilemma

Risk on one side, readers on the other

A comic shop’s margins are thin. Inventory decisions carry real stakes. A single complaint can trigger investigations, legal costs, or reputational damage. On the other hand, pulling titles frustrates fans and narrows the community’s cultural life. Retailers are not censors. They are curators. Laws that blur the boundary between the two force small businesses into an uncomfortable role.

Age-rating and shelving are not cure-alls

Most shops already use age-rating, advisory stickers, and separate shelving to keep mature content away from kids. Those tools work well in practice. They also demonstrate good faith. The problem arises when a statute can be read to criminalize, rather than regulate, borderline imagery regardless of intent or context. At that point, store policies feel like thin shields.

The administrative burden

Compliance is not just about what is on the shelf. It includes training staff, auditing backlist inventory, updating point-of-sale notes, handling parental questions, and documenting decisions. Larger chains can absorb that. Independent shops often cannot. When a law expands the universe of potentially risky items, the cost of doing business goes up. The simplest path becomes the bluntest: pull anything that could possibly draw a complaint.

How AI Complicates The Picture

The promise and peril of generative imagery

SB20’s nod to AI reflects legitimate concerns. Generative models can produce lifelike images with minimal effort. That power can be abused. But including AI alongside print in a single framework also invites confusion. A model that can output new, explicit content on demand is not the same as a 30-year-old manga volume with a brief comic scene. Treating them as interchangeable may help prosecutors, but it burdens bookstores with risks they cannot realistically evaluate.

Collateral damage from broad drafting

When drafters sweep widely to catch AI abuses, analog media become collateral. The result looks like what happened in Weslaco: a book with cultural significance goes behind the counter or disappears entirely. That is not evidence the law is working. It is a signal the net is too wide.

What Communities Can Do Right Now

Encourage transparency from retailers

Open conversations help. If a shop pulls titles, customers should know why. A short statement that explains the law, the shop’s duty of care, and the plan for reviewing inventory builds trust. It also gives readers a way to voice support for careful, case-by-case decisions rather than blanket bans.

Support age-appropriate access instead of broad removal

Communities can ask stores to use common sense solutions. Keep certain volumes behind the counter. Require an ID check for mature titles. Offer parental guides that list potentially sensitive chapters. Those steps respect both the spirit of protection and the value of the art.

Ask lawmakers for clarity

Precision reduces conflict. Legislatures can also create advisory panels that include educators, librarians, retailers, and legal experts to review edge cases before enforcement escalates.

Remember the big picture

The goal should be simple: protect children without hollowing out the shelves. Dragon Ball does not vanish from the culture if a single store pulls a few volumes. But repeated over time, similar decisions shrink access and normalize a climate of fear. Clear rules prevent that drift.

Expert Perspective: How Courts Tend To Look At These Disputes

Context is king

Courts evaluate the work as a whole. A brief scene rarely defines an entire book, especially when it is comedic and not graphic. Judges also consider established cultural value. Longstanding, widely acclaimed works receive serious weight on that score.

Process matters

Enforcement that begins with complaint-driven seizures or criminal charges invites legal challenges.

This is not legal advice

Retailers facing specific questions should consult counsel familiar with Texas law. Every store’s inventory, local norms, and risk tolerance are different. The point here is educational: understand the principles so communities can talk constructively.

Key Takeaways

SB20’s breadth invites cautious overcompliance

When a statute is broad or ambiguous, the safest move can be to remove more than necessary. That is what appears to have happened with Dragon Ball in Weslaco.

Dragon Ball is not the problem

A classic manga with occasional cheeky humor is being treated as risky largely because line-drawing is hard and penalties feel intimidating. That is a policy drafting issue, not a cultural indictment.

Conclusion

Texas’ SB20 was pitched as a shield against obscene material and AI-driven abuses. Yet in practice, its broad wording is pushing some retailers to treat cherished works like Dragon Ball as potential liabilities. That is not a story about a single manga volume. It is a case study in how vague laws can chill ordinary cultural life. The fix does not require choosing between kids and comics.

It requires clarity. Legislators can refine definitions. Retailers can use age-appropriate shelving and transparent policies. Communities can support both protection and access. When the rules are precise, small businesses are not forced to act as censors, readers keep the stories they love, and the law does the job it was meant to do: target actual harm without dimming the shelves.